Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start writing!

Alle Artikel in der Kategorie “Uncategorized”

Why NOT Universal Background Checks?

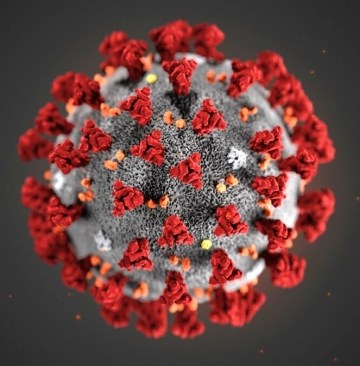

The National Rifle Association (NRA) has painted itself into a corner. In previous spates of mass shootings, when widespread demands were heard for more restrictions on obtaining and owning guns, the NRA loudly (and correctly) declared that it wasn’t people buying guns that was the problem, but the wrong people buying guns. “Don’t attack the Second Amendment rights of people who obey the law,” the Association said in effect. “Stop the ones who are actually causing the trouble: Criminals and people with dangerous mental illnesses.”

The Problem

Absolutely right, so far. But here’s the problem. To most people, the only practical way to do that seems to be through universal background checks (UBC). And the NRA has a cow whenever the idea is proposed. Now that President Biden and the Democratic majority in Congress are again pushing the UBC idea, the question remains, how do you keep the wrong people from getting guns, if you don’t first check to make sure people who are getting guns aren’t the “wrong people”?

Gun control advocates mistaken.y believe that firearms sales at gun shows are exempt from background checks. But this is false. Most sales at such shows actually do require background checks.

Right now my Second Amendment friends are afraid I am about to drink the background-check Kool-Aid. Yes, I would be in favor of universal background checks–in principle. But don’t judge until you hear the rest of the story. Because, for me to be in favor of UBCs they would have to be done exactly right. The question is, can they be? We shall see.

Why background checks?

So what do I mean by “exactly right”? Let’s start with what we want to have in a background check policy. It should be as thorough as possible–we don’t want anyone with a felony record slipping through the cracks and getting a gun. We don’t want anyone with a history of violent mental illness, nor someone who is a domestic abuser, nor a person who is abusing controlled psychoactive substances; nor anyone else who clearly ought not to get their hands on a potentially lethal tool to be able to get a gun.

What we want to avoid

Okay, that’s the easy part. But what don’t we want to see?

1) We don’t want a background check law to lead to any kind of firearms registry.

What does that mean? Second Amendment supporters have long opposed any move to allow the federal government to register some or all privately-owned firearms. True, such a data base could be of assistance to law enforcement nationwide. It might make it easier to track down criminals and misused weapons.

Unfortunately, it would also make it easier to track and confiscate firearms from anyone, even if they’re not criminals, should things ever go sideways between us and those who govern us.

You might now be saying, “Well, that is strictly hypothetical. And really, nothing like that could happen here!” I’ll handle the “Can’t happen here” argument in another article (in other words, don’t assume too quickly that it can’t happen here). But for the time being, I’ll admit such a circumstance is hypothetical–and has been hypothetical for most of our history. But maybe it has remained hypothetical for so many years, because no such registry exists. If there is one thing we learn from the Past, it is that no government stays benign forever–just ask the Romans (or the Weimar Republic–or any number of countries that have slipped into chaos even in the past few decades). It may well be the inability of the government to track privately-owned firearms in this country that has helped keep that scenario hypothetical.

Firearm background check form being filled out. One objection to an expanded law is that the current law isn’t being properly administered, allowing people to buy guns they shouldn’t have.

“But,” you might continue, “How will we know whether it will work if we don’t at least try it?” My answer to that is, in the case that things do someday go sideways, it will be too late to change back. Think of it like a game of Russian roulette. You put a cartridge in a revolver and spin the cylinder. You now have one chance in six of shooting yourself if you go on to play that idiotic game. The problem is, you don’t know if that one-in-six will happen on the last trigger pull, the third pull–or the first one! Giving the government such comprehensive access is very much like playing Russian roulette. Eventually the hammer is likely to fall on a cylinder that isn’t empty.

There is also a rights issue associated with this. Can you imagine the outcry if a law was passed requiring publishers to register their printing presses and private citizens to register their computers and printers? Before you say guns are different, consider the power that the press has exercised against governments in the past. Which is why totalitarian regimes impose very strict controls on both the press and firearms ownership.

The worry that the NRA and others have is that a UBC law could easily lead to such a registry

It would work this way: In order to be sure the check was universal, there would have to be an accessible record of every transaction, including what firearm exchanged hands and why, and who the parties to the transaction were. Otherwise, when asked “Did you get a background check to buy that gun?” someone could simply say, “Sure, I got a background check!” If there was no record, you’d just have to take the person’s word for it. Without a record accessible to government, the law would have no material effect on the problem it was meant to solve. That means that most proposed universal background check ideas would inevitably have to lead to a firearms registration of some sort to make any difference.

2) It shouldn’t add additional cost to a firearms transfer.

This is one of my concerns with the current background check law. It allows for federal firearms license holders to charge a fee for their services and to offset any costs they incur in doing the background check. You may at first think that is reasonable. There may be, after all, costs associated with the process, and people performing the service ought to get some compensation for it.

But there is a glaring problem with this. Firearms ownership by otherwise unrestricted citizens is an inherent, constitutional right. Owning a gun is not the same thing as owning a car, a stew pot, or a porch swing. The right to own firearms is written into the constitution. Requiring universal background checks, and attaching a cost to it, is essentially taxing citizens to exercise a constitutional right.

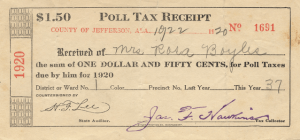

Some might argue that firearms sales are subject to sales taxes. Doesn’t that amount to the same thing? Not really. Sales tax is not a condition for owning a firearm. A clean background check would be such a requirement, and charging for the check would be the equivalent of taxing you to exercise your rights.

Paying for background checks for firearms bears similarity to unconstitutional poll taxes.

Acknowledging that a gun is different than a printing press (though each is essential to the exercise of its respective Amendment), still it would be same thing in principle as requiring a background check to buy a printing press, and charging the buyer to perform that check. This brings to mind the trouble over poll taxes in America’s past, where you had to pay to exercise your right to vote. Even people who are opposed to gun ownership should be concerned about the precedent improperly-constructed UBCs might establish

Should a UBC law indeed come to pass, cost for it ought to come exclusively from the federal budget (and thus be born by all American citizens), since it would be the federal government that created the requirement with the intention of protecting everyone’s public safety. Citizens exercising a right should not be financially penalized for complying with a legally-imposed obligation in exercising that right. That was precisely the issue with poll taxes.

3) It should not cause an undue burden for those legally transferring a firearm.

There are some states that have already instituted their own universal background checks. Some are so draconian that, for example, if you wanted to borrow your brother’s deer rifle to go hunting, you would have to go down together to a local Federal Firearms License (FFL) dealer, pay the fee and have a background check done on you before your brother could hand you the rifle. And then, when you were done hunting, the two of you would have to go back to an FFL, pay the fee and have a check done on your brother before you could give him his own rifle back! Any federal UBC law would have a provide for straightforward situations like this. (Note that recently proposed UBC laws do make allowances for this such transfers within close relationships.)

4) It should not create a large burden on the federal government by requiring either creation of a huge new agency or requiring the massive expansion of the current NICS (for “National Instant Criminal Background Check System”) process.

This is one of several complaints the NRA and others raise. Creating UBC system would almost certainly be expensive and require a large addition to the federal bureaucracy. I’m not altogether sure this is as big an objection as some maintain. Yes, it would add significantly to the federal workforce. If it did result in saving many lives, though, maybe it would still be worth it. On the other hand, if an equal or greater beneficial effect could be achieved without growing the bureaucracy, that would be preferable. Which leads us to the final point:

5) It would have to actually work.

That’s a deal-breaker argument against universal background checks: Because they don’t work (notice, I didn’t say “won’t”–I said “don’t”). The NRA contends that no background check law, no matter how universal, will keep all criminals from getting guns. That’s true. But the NRA may be wrong to reject them only because they won’t prevent every criminal from getting a gun. They may still prevent many criminals–plus many of those who are seriously mentally ill and others who shouldn’t have them for various reasons–from getting firearms.

A perfect spot for gun exchanges without background checks. No one would ever know.

However, there is evidence that UBCs might not have much of an effect at all. That would be a show-stopper. As I touched on earlier, guaranteeing that background checks are actually done when guns change hands in private is nearly impossible. There is really nothing to stop private parties from meeting in a dark alley for a transaction. Sure, it would be illegal, but how would you prove that it happened

Imagine spending all those tax dollars and hiring all those people to create a UBC program, then putting every law-abiding citizen who wants to purchase a firearm through the hassle of undergoing a background check—and then discovering it had no actual effect on crimes committed with guns? Some states that adopted such laws have found just that

Is there something better?

So, after all this, I have to tell you this straight: Though it would be awesome if those five criteria I listed earlier could be met, from what I can see no background-check law proposed so far could possibly do it.

Nevertheless, there is extensive support nation-wide for a UBC law. Its shortcomings aren’t even seriously being considered by the voices demanding these new laws most loudly. Unless some more effective, less objectionable alternative is found, universal background check laws with all their imperfections are beginning to look inevitable

But I have an alternative to suggest that would avoid most, or all of these problems. And it would be more effective besides. Stay tuned for Part 2.

There is Going to be a Disaster–You Might as Well Get Ready For It!

(Note: This may seem like a departure from my usual Second Amendment musings; but my “Shaking Up the Zombies” blog was also meant as a home for occasional discussion of emergency preparation and self-reliance. That’s definitely relevant here.)

When my wife and I got on the plane to travel from Austin, Texas where we lived at the time to the town of Frederick near the Maryland/Pennsylvania border, we knew there was a storm coming but didn’t yet know we were heading for ground zero. Four days later we found ourselves hunkered down in a pitch-black house while gale force winds shook the walls and howled around the windows. Along with my son, his wife, and his two little girls, we lived one long night watching and listening as the trees thrashed and twisted and sheets of horizontal rain driven by the mutant hurricane Sandy throbbed against the siding.

While wives and babies huddled under the covers to keep warm ahead of the creeping cold that the knocked-out heating system no longer held at bay, my son James and I stayed up into the wee hours to make sure everything stayed battened down. Our only entertainment was watching electrical transformers flash blue and die against the horizon. James’s power was among the first in the area to go, even before the main force of the storm officially hit. Four days later it was still out – and would be for another week or more. Thankfully, other than the electricity, no serious damage resulted in James’s neighborhood.

But, along with the rising Monocacy River which had taken out the power poles for James’s subdivision, came some startling insights as well—among them just how unprepared many Americans are for even relatively limited emergencies. James had spent several years as a Boy Scout and should have “been prepared.” But the demands of keeping pace with modern American life had caught up with him and his family. Knowing that under normal conditions the power was always on and one could just run out to the store for whatever one was short of, he had few food reserves, only one working flashlight, and no way to cook food or even heat a cup of water during a power failure. For room light he had only decorative candles.